Modern architecture, as examined through the critical lens of Beatriz Colomina, is not simply a solution to functional needs but rather a complex, mediating mechanism designed to manage the acute psycho-social crises generated by metropolitan life. This framework begins with the foundational sociological diagnosis provided by Georg Simmel (1858–1918), whose analysis of the city dictates the psychological demands placed upon modern architecture.

Simmel diagnosed the metropolitan environment as characterized by an “intensification of nervous stimulation.” The sheer density, rapidity, and constant succession of sensory impressions inherent in urban existence place an enormous strain on the individual psyche. This sensory overload necessitates a defensive mechanism to prevent the individual from being overwhelmed and worn out by the “social-technological mechanism” of the large city.

The required psychological response is intellectualism. Simmel observed that the intellectual life and the money economy are intrinsically connected. The metropolitan individual, steeped in the “pecuniary principle,” learns to prioritize rationality, quantification, calculability, and exactness. Money, being concerned only with what is common to all (exchange value), reduces all quality and individuality to the question of “how much?” Emotional, intimate relations, founded on individuality, are superseded by rational, detached relations where man is “reckoned with like a number.” This intense demand for calculation and punctuality is forced upon metropolitan existence by its sheer complexity and extension.

This need for emotional disengagement and rational defense has a critical implication for architectural valuation. If the modern subject must rely on quantification to maintain psychological balance amidst urban chaos, then architectural criteria must necessarily shift toward the measurable and standardized. This sociological pressure provides the structural justification for Le Corbusier (1887–1965)’s subsequent appeal to objective metrics, industrial standards, and quantifiable data—even in arguments concerning subjective experience, such as light and view. The emotional detachment of the metropolitan subject is, in this sense, mirrored and mandated by the intellectualist requirements of the modern dwelling, transforming the machine à habiter into a psychic defense system predicated on objectivity.

The inherent density and compressed physical space of the city create a profound paradox: while there is “bodily proximity and narrowness of space,” this very closeness mandates a heightened “mental distance,” manifesting as “reciprocal reserve and indifference.” This need to preserve the autonomy and individuality of existence in the face of “overwhelming social forces” constitutes the deepest problem of modern life.

The ultimate form of nervous defense developed by the metropolitan personality is the “blasé attitude.” This is not simply lack of perception, but a deliberate “blunting of discrimination” wherein the differing values and meanings of things are experienced as “insubstantial.” Everything appears in an “evenly flat and gray tone,” allowing the individual to refuse to react to constant stimulation, protecting the self from being “leveled down” by external pressures. Simmel observed that the freedom derived from this indifference comes at a high price: the “devaluing of the whole objective world,” which eventually drags the individual’s own personality down into a feeling of worthlessness.

The architectural project of modernity must respond to this crisis of the private self. The fundamental task is to “solve the equation” set up between the individual and the “super-individual contents of life,” effectively determining how the personality accommodates itself to external forces. The modern dwelling, therefore, becomes the critical site where the inside (the unique, reserved personality) attempts to negotiate with the overwhelming outside (the calculated, indifferent public sphere). Colomina demonstrates that architects like Adolf Loos (1870–1933) sought to enforce this Simmelian reserve, while Le Corbusier, through media, effectively codified the architectural abandonment of that reserve, transitioning from a politics of defense to one of exposure and domination.

Architecture as Mass Media: Colomina’s Methodological Revolution

Colomina’s central contribution to architectural theory is the assertion that Modern Architecture’s modernity derives intrinsically from its engagement with mass media. This shift mandates that the object of study for the architectural historian must extend beyond the physical building and the architect’s biography to encompass the publications, photographs, films, and exhibitions that constitute the architecture’s public life.

The Building as Communication and Representation

Colomina argues explicitly that a building should be understood in the same terms as “drawings, photographs, writing, films, and advertisements.” The architectural structure is fundamentally a “mechanism of representation in its own right” and a “construction,” both physically and conceptually. Traditional architectural thought failed to recognize that architecture was heavily influenced by mass media, such as photography and advertising.

By treating the building as a medium of representation, the classical boundaries between subject and object are fundamentally challenged. When these boundaries “undermine each other,” the objecthood of the building itself is called into question, thereby challenging “the unity of the classical subject presumed to be outside of it.” The crucial question driving the discussion of domesticity then becomes not merely how to create shelter, but how to construct the “home” in terms of privacy versus publicity—is it a private refuge of anonymity, or an extension of public life and spectacle?.

The existence of the architectural avant-garde was predicated upon this media engagement. Influential figures like Le Corbusier, Adolf Loos, and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886–1969) gained recognition not merely through built structures, but through their influential writings and manifestos published in journals and magazines. The work, in many cases, “did not exist before its publication.” The manifesto, whether written or materialized as a temporary exhibition pavilion, was the primary vehicle for self-invention and debate.

Photography, Utopia, and the Threshold of Decay

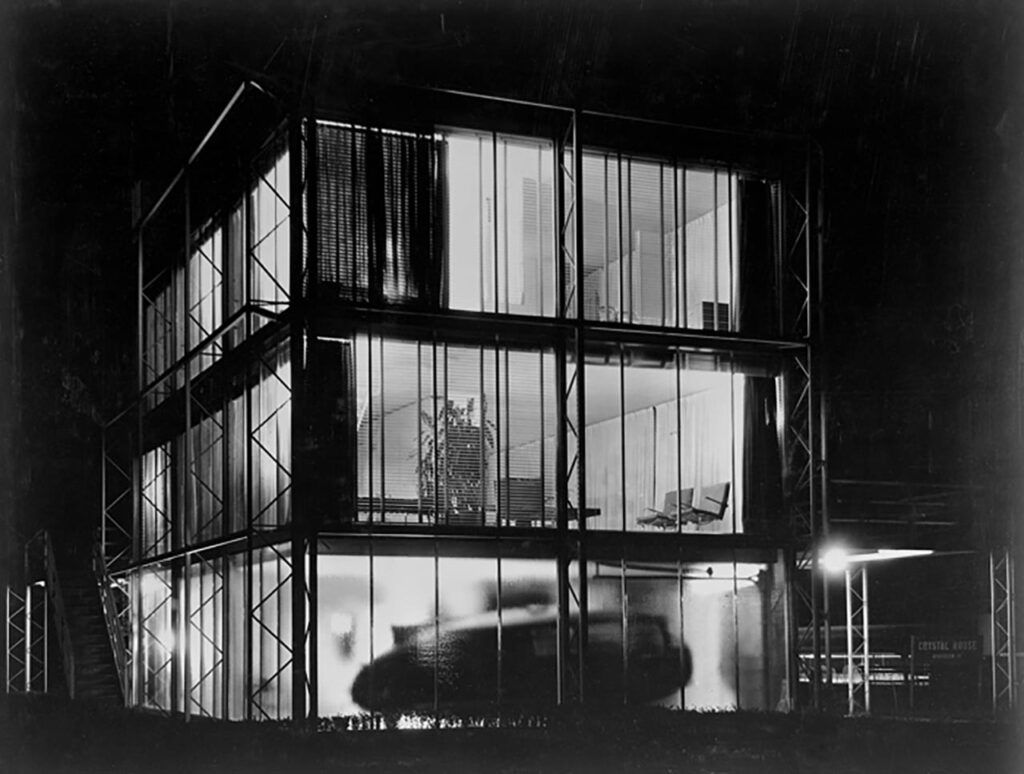

This focus on media reveals a profound paradox concerning the physical durability of modern architecture. Modern structures were often designed to generate aesthetically pleasing photographs, communicating the abstract, utopian ideal of modernity by appearing like pristine, standardized “cardboard models.”

However, in reality, modern architecture was built with inherent fragility. Colomina notes a critical distinction in temporality: modern architecture “starts to fall apart the moment it is built,” much like a newspaper that begins to disintegrate upon reading. The “immaculate empty surfaces” immediately betrayed their own imperfections through decay. The physical, lived object is inherently unstable and finite, residing in a “threshold of undoing itself.”

It is here that the photographic representation assumes primacy. The enduring artifact of modern architecture is the distributed image, not the localized physical object. Photographs preserve the vision of “endless optimism, the utopian dream of the architect.” Even when decay is depicted, such as in Bernard Tschumi’s photograph of the derelict Villa Savoye, the image itself becomes the enduring statement—a paradoxical manifesto asserting that “The most architectural thing about this building is the state of decay in which it is.” The built structure is fragile and localized, but the image is permanent and ubiquitous, confirming the media-centric position that the architect’s true project lies in communication and representation, not merely construction.

The Loosian Interlude: Defending the Interior Gaze

In contrast to Le Corbusier’s later embrace of publicity, Adolf Loos is interpreted as the architect of Simmelian defense. Loos’s architecture attempts to maintain the necessary psychological distance required in the metropolis by designing a deliberately inward-focused gaze.

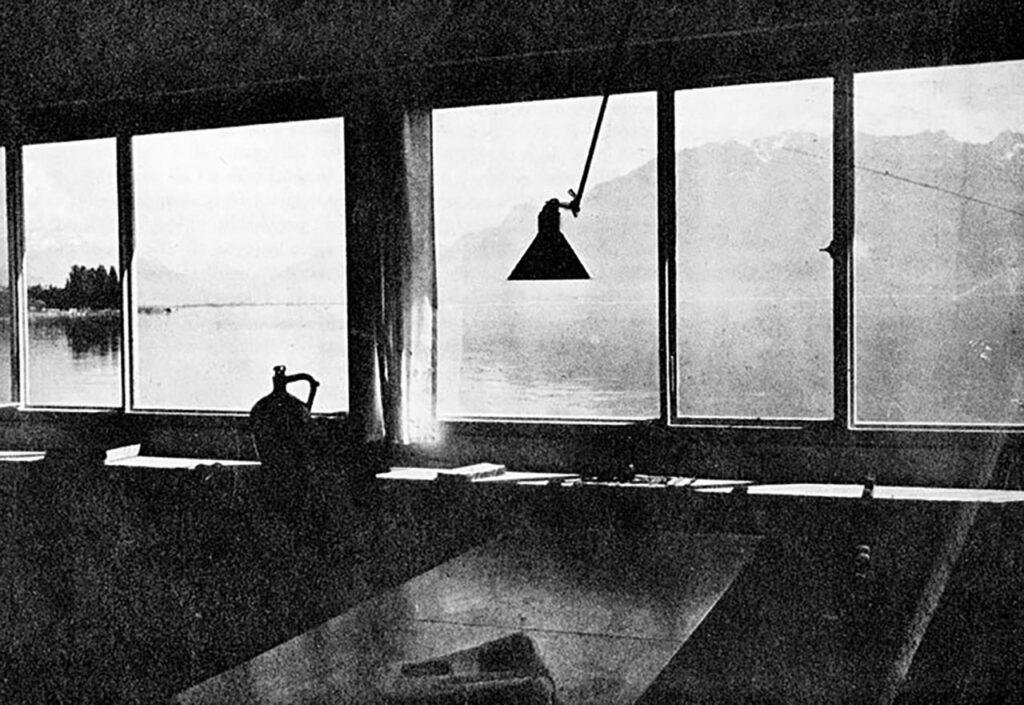

Loos achieved this primarily through the use of specific fenestration strategies. His windows were frequently opaque or covered with sheer curtains, serving only “to let the light in, not to let the gaze pass through,” thereby resisting the external world’s intrusion and upholding a Loosian system of “defensiveness.” This strategy involves an ambiguity between reality and illusion, often facilitated by mirrors, and a critical separation of sight from the other senses.

Furthermore, Loosian interiors strategically arrest the occupant’s movement and vision. In houses like the Müller house, the organization of space and the disposition of built-in furniture force the occupants into “precise, static positions,” often sitting with their backs to the window and facing the room. This forces the body to continually turn around upon entering a space, facing the area just traversed rather than the space ahead or the outside world. This architectural choreography demands that the space be comprehended by “occupation,” emphasizing the subjective, psychologically secure interior experience. The couch placement, such as in the Moller house, produces a sense of psychological security, offering a comfortable nook for reading, sheltered from the world.

Le Corbusier: The Modern House as a Photographic Apparatus

Le Corbusier represents a decisive break from the Loosian defense, transforming the house from a psychologically protective interior into an apparatus of classification, external domination, and mass media projection.

Purism, Standardization, and the Gendered Gaze

Le Corbusier’s Purist project was fundamentally reliant on industrial standardization, evident in his meticulous collection and use of industrial catalogues featuring automobiles, airplanes, office furniture, and other mass-produced goods. This celebration of the standardized object was tied to an aesthetic of exposure. Le Corbusier’s “Law of Ripolin” advocated for stripping away “outdated ornamentation” to reveal the smooth, modern object.

However, this exposure was not a complete removal of cover; the white paint functioned as a thin “veil.” Colomina critiques this transparency as a mechanism of control and display, arguing that Le Corbusier exposed the architectural body, which is implicitly feminized, to the “penetrative gaze of men.” This positioning frames the utopian, perfect rooms as theatrical sets for domestic dramas.

The Horizontal Window: Categorical Vision and Mechanized Sight

The most significant shift in Le Corbusier’s architecture pertaining to the inside/outside dichotomy is the introduction of the fenêtre en longueur, or the horizontal window. This element fundamentally alters the relationship between the subject, the house, and the landscape. Le Corbusier argued against the vertical window (la porte fenêtre), which, according to Auguste Perret (1874-1954), reproduced an impression of complete space by including views of the street, garden, and sky—the space of traditional perspective.

The horizontal window, by contrast, crops the cone of vision, specifically cutting out the strips of sky and foreground that sustain the illusion of perspectival depth. The Corbusian window corresponds directly “to the space of photography,” effectively framing the landscape as a standardized image.

Le Corbusier justified this technological shift not through emotional or qualitative argument, but through scientific objectivity, relying on a photographer’s chart giving times of exposure to “demonstrate” that the horizontal window illuminates better than the vertical. Subjective observation is replaced by objective, mechanical metrics. The house is transformed into a “system for taking pictures.” Le Corbusier explicitly saw the window as a camera lens, ready to be “diaphragmed at will” to control light.

The consequence of this mechanized observation is the establishment of the “categorical view,” where the view from the house is “without connection with the ground, or with the man behind the camera.” The traditional, embodied subjectivity of the resident is replaced by the detached, free-floating gaze of a photographic camera. This mechanized sight aligns the architectural project perfectly with the intellectualist, pecuniary subject demanded by Simmel’s metropolis. By substituting the emotional, personal relationship with the landscape for a system of objective classification, Le Corbusier creates a detached operator whose “horizontal gaze leads far away” toward “dominating a world in order” from a skyscraper perch. This technological dominion replaces the psychological need for defensive reserve with mechanical control.

The Tourist Occupant and the House as Exhibition

In the Corbusian dwelling, the inhabitant is deliberately displaced. At Villa Savoye, the occupant is conceived primarily as a “visitor.” Le Corbusier noted that visitors often feel disoriented, failing to recognize what they see and feel as a “house.” Unlike the Loosian subject, who is both actor and spectator, the Corbusian subject is “detached from the house,” which itself becomes “the object of contemplation,” akin to a gallery.

Le Corbusier’s confidence in new media justified the complete abandonment of physical defense. He argued that the new urban conditions, dictated by media such as telephones, cables, and radios—which he called “machines for abolishing time and space”—rendered the physical “defensiveness” of a Loosian system unnecessary. Control has migrated from the thick, defensive wall to the invisible network media.

The Ghost in the Architectural Machine: Technology, Exposure, and the Body

The phrase “ghost in the machine,” coined by Gilbert Ryle (1900–1976), refers to the fundamental philosophical error—the “category mistake”—of Cartesian mind-body dualism. Ryle argued that the dogma mistakenly represents mental facts as if they belong to one logical category (like a substance) when they belong to another entirely. Colomina’s work transposes this philosophical error onto the technological and spatial logic of modern architecture, revealing that the clean, rational machine of modern design is haunted by its own invisible, operating systems and erased histories.

Invisible Power and Mechanical Control

Modern architecture, particularly in the Corbusian model, functions as a body (the visible structure) whose operational capacity (the mind) is systematically rendered invisible and mechanical. Le Corbusier formalized this category mistake by explicitly separating sensory and bodily functions from mechanical operation. He asserted, “A window is to give light, not to ventilate! To ventilate we use machines; it is mechanics, it is physics.”

This separation is paramount, as it externalizes the critical functions of dwelling into unseen mechanical networks. Power shifts away from the visible, protective structures and into the “invisible” realm of modern media. Modern technology, such as electricity, is described as an “invisible, modern power” that “actionne les portes et déplace les murailles” (operates the doors and moves the walls) without providing visible illumination. The look of “domination” promised from Le Corbusier’s skyscrapers is mediated and controlled by these unseen forces—the telephone, cables, and radio—which abolish time and space.

The structural logic of modernism thus becomes an architectural category mistake. The house appears to be a physical, bounded object (the machine), yet its true function, control, and agency are outsourced to an unseen, technological network (the ghost). The inhabitant, having been disoriented and detached (the visitor), is placed under the dominion of this technological “ghost in the machine,” wherein the physical structure is merely a display case for the effects of invisible operational forces.

X-Ray Architecture: Transparency, Pathological Exposure, and the Body

This interest in the invisible mechanical core extends to an obsession with pathological exposure, which Colomina explores in her concept of “X-Ray Architecture.” The development and wide use of X-rays—often linked to the diagnosis of tuberculosis—fostered an architectural imagination of absolute transparency. Modern design actively engaged with the “biology of the machine world” and used disease imagery to express concerns for social order.

The invention of X-rays was perceived as a violent “intrusion into the intimacy of the body.” Modernist glass and transparent walls transposed this medical technology onto the built environment, proposing a “crystalline stage” for humankind. This architectural transparency is not purely utopian; it exposes the negative dimension of modern clarity by forcing the internal structure—and the intimate life within—into public display. This blurring of boundaries creates an “occupiable blur” where the building envelope fades away, leaving Richard Buckminster Fuller(1895–1983)’s car, for example, occupying the nebulous space between inside and outside.

The Historical Ghosts: Gendered Invisibility and Labor

Colomina further utilizes the “ghost” metaphor to critique the social and historical erasures within Modernism. The category mistake of dualism not only separates mind from body but also intellect (the genius architect) from uncredited labor (the collaborative body). Colomina identifies women as the “ghosts of modern architecture,” present and “crucial,” yet “strangely invisible” in the official record.

Architecture is inherently a “deeply collaborative” practice, often resembling moviemaking in its complexity, yet this is traditionally guarded as a secret. The prevailing narrative, focused on the sole male genius, commits a systemic historical erasure. Correcting this record is not merely a matter of historical accuracy or justice, but of recognizing the “productive complexity” of the field. The philosophical category mistake of separating the mind (design intent) from the body (execution and collaboration) serves to perpetuate a narrative where the masculine authorial “mind” is privileged, while the material, often gendered, “body” of labor and collaboration is destined to “haunt the field forever.”

The Mediated Condition and Post-Digital Architecture

The exhaustive analysis of Modernity through Colomina’s perspective reveals that the architectural project of the early twentieth century was fundamentally a crisis of mediation. Georg Simmel established the psychological necessity for reserve and intellectual defense in the overwhelming metropolis. Adolf Loos responded with an architecture dedicated to enforcing psychological privacy, creating an inwardly focused, secure interior. Le Corbusier, however, utilized mass media—photography, standardization, and networking technologies—to dismantle this defense.

Le Corbusier’s architecture functions as a rational machine for classifying the world, replacing subjective presence with objective measurement and turning the house into a technological apparatus. This resulted in an architectural category mistake—the “ghost in the machine”—where invisible mechanical systems governed the visible structure, subjecting the detached occupant to unseen forces. Furthermore, the modern aesthetic of transparency, amplified by the X-ray imagination, pushed this media function to a pathological extreme, exposing the body and dissolving the Simmelian requirement for psychological reserve. The privacy sought by the classical subject was structurally abolished, replaced by a permanent state of publicity.

The legacy of this media-driven modernity continues to shape contemporary life. The Corbusian project of total connectivity and exposure is fully realized in the digital age. Colomina suggests that new forms of architectural manifestos will inevitably emerge from the “culture of sharing” and electronic media of today. The boundary between inside and outside, private and public, established by the mechanical systems and photographic frames of the 1920s, has now been irrevocably replaced by a condition of total, networked transparency. The modern house, conceived as a camera, has evolved into a permanently broadcasting device, confirming that the building’s essential nature lies not in its physical enclosure, but in its capacity for communication and perpetual display.